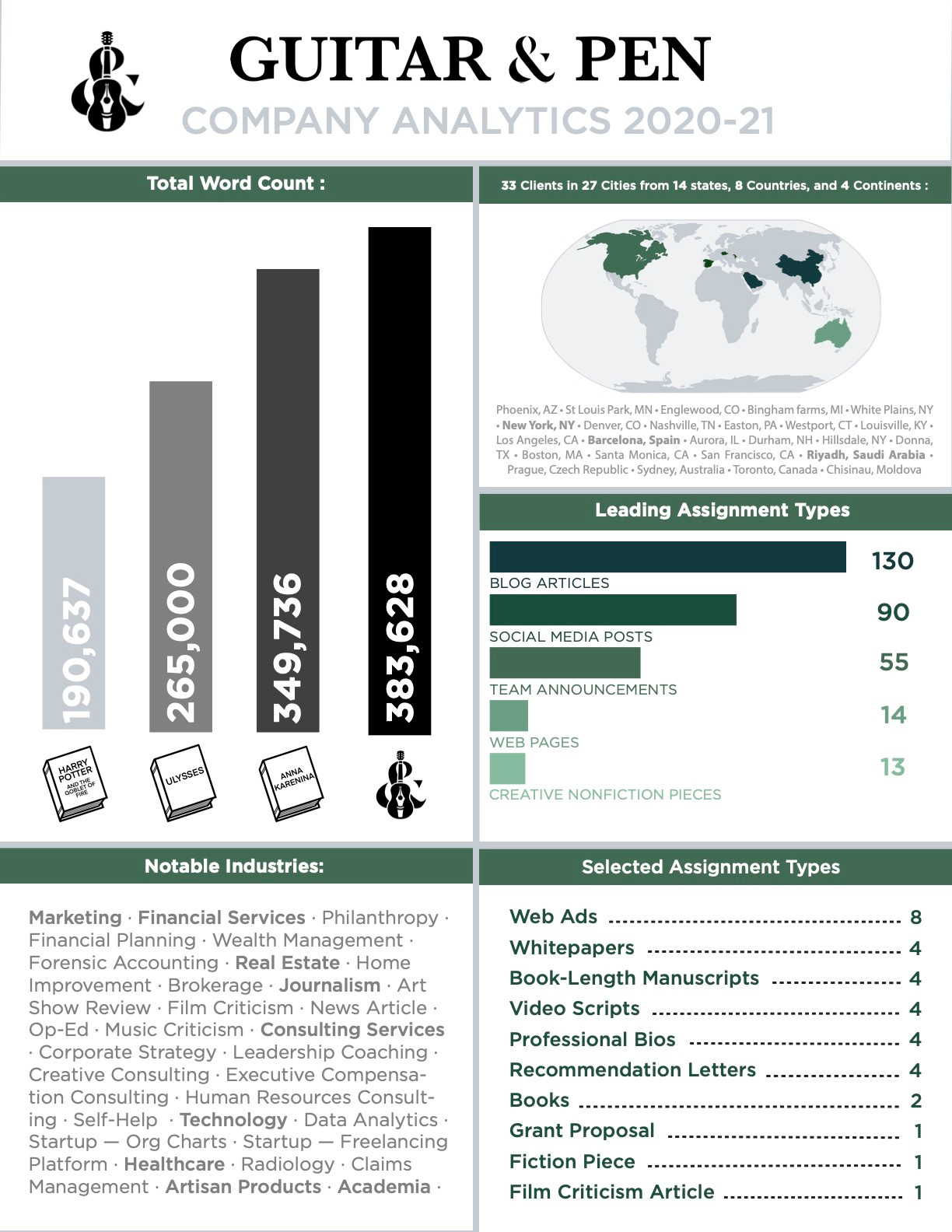

Because I knew it was a lot, I tabulated the work I did in Guitar & Pen’s first year. I reopened every assignment, copied their specs into a giant Excel spreadsheet, and performed what rudimentary data analysis a mathophobe-cum-freelance-writer like me can.

By way of introduction: I’m a freelance writer and musician. I’ve been writing creatively ever since I learned how to write. I’ve been writing professionally since Fall 2018. For two years, I lived in Nashville, trying to become a career singer/songwriter. After getting spiritually depleted by the pursuit (full story here), I went back to school, getting an MFA in writing from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. I graduated in May 2020, just as COVID-19 shut down much of the US. Unable to find a full-time job, I ramped up my freelance business a year ago, and it has since become my full-time pursuit.

And now, without further ado…

The Data

“Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.”

— Albert Einstein, freelance scientist

The Lessons

1. People Are Knowable

Because we live in isolated minds, it’s easy to think that we’ll never know each other. It’s also easy to think solipsistically — I’m the only real person in the world — an inherently vain belief, driven by the notion, stated or unstated, that this mind you’re in is somehow superior. It’s also easy to determine that, since we’ll never know every single thing another person has thought or done, that we’ll never truly know that person.

I don’t believe any of that. Because I believe that humans want and need almost identical things — Comfort and Company — I start each relationship, whether business or personal, on the assumption that I know this person. I know what they’re trying to get, and I know that whatever their methods — their line of business, aesthetic choices, social mannerisms, etc. — all are targeted fundamentally at these things.

My job has me writing for — or as — clients whose lives look almost nothing like mine. I’ve written for white men who grew up privileged, and I’ve written for women of color who grew up disadvantaged. I’ve written for attorneys, wealth advisors, HR consultants, self-help gurus, and startup entrepreneurs. They live on different continents, they speak different languages, they’re oppressed by different inner and outer forces. But they’re the same: They all want comfort, they all want company, and they’ve all developed methods for getting them and/or extending them to others.

People are knowable. I believed this before I started, and I believe it all the more one year in.

2. Technicalities Are Learnable

Different clients require different levels of technical knowledge. One in particular, a data analytics giant, took hours of background research to comprehend; others take only a 30-minute interview. Whatever it takes, my objective is not necessarily to become an expert. My objective is to become an informed layperson.

Potential customers don’t need to understand every single nuance of your business. They only need to understand why they need you. Therefore, I don’t need to understand every nuance of your business. It helps if I know more than the average consumer, so that I can write at a level of relative authority. But it also helps if I approach your topic from a layperson’s perspective, as laypeople are your target audience.

For example, I have one client in the mortgage subservicing space. Mortgage subservicing is a remarkably arcane business. If you really want to know, it’s a form of outsourcing that mortgage lenders use so that they can spend their time originating more loans, not servicing the ones they already have. Servicing is hard — it takes deep knowledge of regulations, warm personal relationships with homeowners, and the ability to evolve as new Presidential administrations change the rules. Good servicing takes specialists.

To write well for this client, I don’t need to understand every regulation. I need to understand why their offering is necessary to their clients. Mortgage subservicers are really selling peace of mind: comfort in homeowners that the roofs over their heads won’t cave in, and comfort to lenders that the loans on their books will stay healthy.

After comprehending that, I dove into specifics. I learned about their methods, their tech, and the regulatory backdrops (e.g.: The Biden administration will be stricter toward subservicers than the Trump administration was). I learn about the forces that drive them and contain them.

It may sound obtuse, but the bottom line is that all of this was designed by humans, is run by humans, and needs to be communicated to humans. Humans aren’t that complicated. We all want comfort and company. Our differences stem mostly from our relative limitations (self-imposed and institutionally driven) on the path to getting them. Writing well for this client takes some level of grueling self-education, but not as much as you might think.

3. Language Is Essential

I hold certain truths to be self-evident:

First: Every living entity needs language. At least until Elon Musk delivers on his promise that Neuralink will obviate the need for conversation, language is both lock and key. It connects minds. When minds feel private, life feels lonely, meaningless. When minds feel unified, life feels populous, meaningful. Language is the connective medium.

Second: Better language means better connections. Connection is blighted by misunderstandings. Misunderstandings are the product of poor language. A wrong word conveys a wrong idea; a suboptimal word paints a subpar portrait. Language that both informs and sings creates instructive, colorful connections.

Third: Relationships drive happiness, in business and in life. Yelp recently determined that “great service” is the primary driver for 5-star reviews. If a person or a product demonstrates investment in your personal wellbeing, it creates happiness, loyalty, repeat business, enduring friendship, everlasting love — you know, the good stuff.

So: All entities, regardless of size, industry, or location, can drive excellent business by investing in excellent language.

My first year bore out these beliefs. In a mere 12 months, I worked for clients in 25 lines of business, broken into nine major industries. Of those nine industries, I have received formal training in precisely one (Journalism). Why was I qualified to write about the others? Because each shared a common trait: They wanted to drive excellent business by investing in excellent language.

In Summary

In truth, I believed much of this before my year of intense word-production. But after averaging more than 1,000 words per day for a range of clients diverse in demographic, industry, location, and more, my beliefs have only strengthened.

As I wrote for people with decades of experience in fields I’d never researched, I doubted whether people were knowable. As I wrote copy for companies in exceptionally arcane fields, I doubted whether technicalities were learnable. And as I struggled through client relationships that didn’t quite work out, I doubted whether language — or my kind of language — was essential.

Finally, doubts are just that — not timeworn truths about the world, just dark voices that seek to undermine their speaker. They’re natural, inevitable, insuppressible; but with enough evidence, they can be overruled.

The data above is my evidence so far. Each day, I accumulate more and more, each datum a brick in my lifetime edifice, my modest tribute to language.

Excellent, once again

Dustin, this is brilliant! I've been freelancing writing longer than you've been alive, and I've learned all these lessons too. But I could not have articulated them as well. You nailed it. This should be required reading for anyone who thinks, "Hey! I like to write! I can be a writer!"

Well done, my friend.