But first…

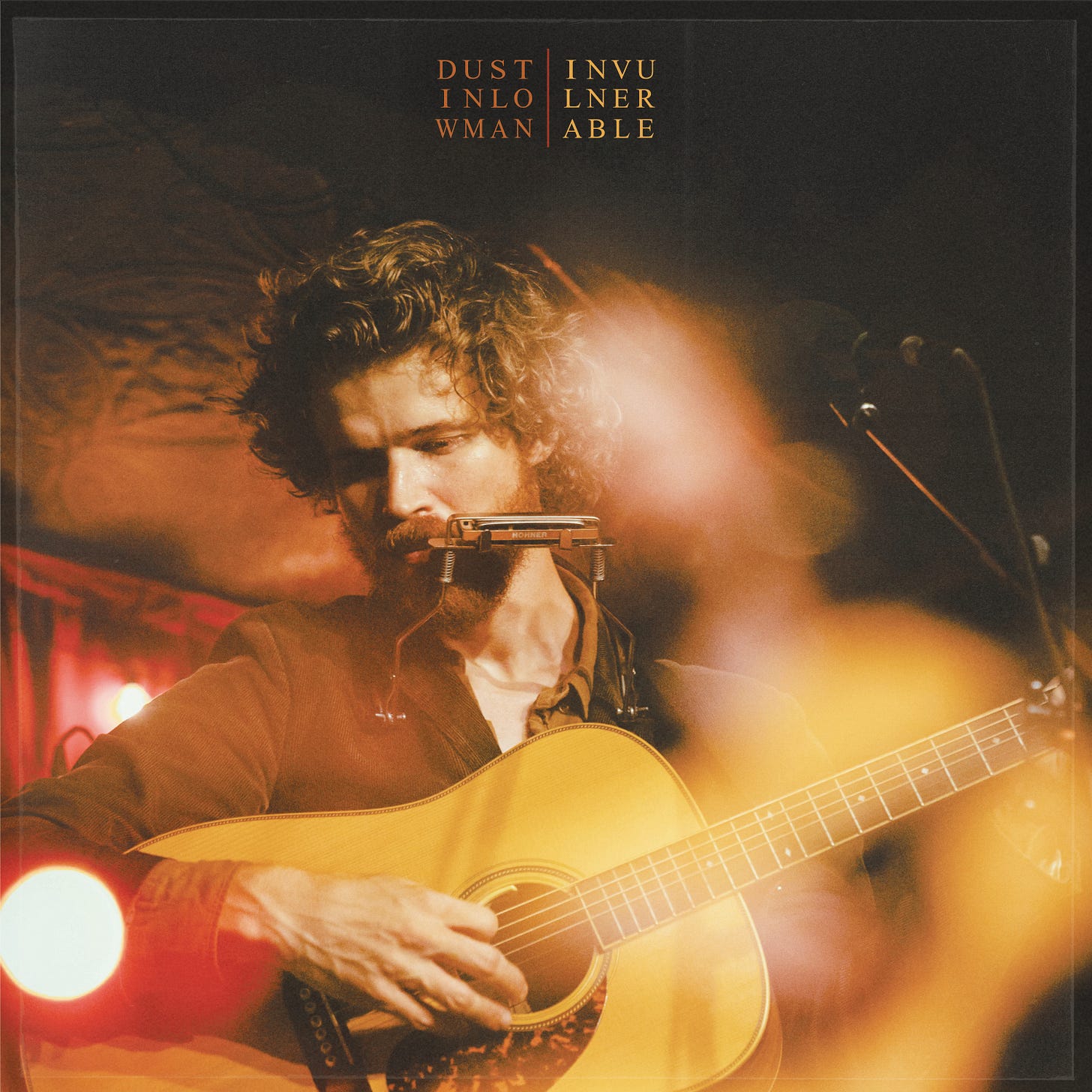

Stream “Invulnerable” on Spotify!

See why NPR, No Depression, and Twangville have featured new album “Invulnerable” and its tracks in their hallowed outlets.

“Do you even like any of these albums?”

Someone I don’t know posted this comment after watching a 90ish-second Instagram video in which I critiqued and graded Bob Dylan’s 1976 album, Desire. Desire is the quintessence, for me, of a certain kind of album: one where I love certain songs, like others, and despise a couple, leaving me with an array of mixed feelings. How could the same poet that spun the madcap “Black Diamond Bay,” an epic of darkly comedic, byzantine detail, have written something as brainless as “Joey”? How could the auteur of Blood on the Tracks, one of rock’s greatest love-is-over-now-what albums, have written as superficial a romantic ballad as “Sara”?

Desire has always left me with unresolved feelings — especially compared to a work like Highway 61 Revisited, which leaves me feeling practically nothing but poetic awe. In my 90ish-second video on Desire, I attempted to describe my mix of awe and incredulity and then render an overarching “grade” of the album in the form of a tier list ranking.

If you’re unfamiliar with the concept of a tier list, it’s a system of ranking that arose in the video game world. In it, players would rank aspects of a particular game. Super Smash Bros. Melee players, for example, would rank Pikachu, Mario, Sheik, Ganondorf, and the rest of the game’s fighters according to their strength. The ranking system goes by letter, where “S” (a Japanese demarcation of high quality) is the best, and “F” is the worst. The tier list has lately transcended the video game world, and now cyber pundits from Fortnite diehards to Neil Degrasse-Tyson to Dylan freaks like me — and beyond — use them.

Tier listing is essentially grading. Anyone who’s spent any time in a school system knows the simultaneously seductive and frustrating qualities of grading: It feels sublime to get an A, it feels crappy to get an F, and all the while, it feels absurd to be subjected to so limited a method of evaluating human beings. Like the capitalist system under which we all toil, grading is a deeply flawed framework, but, obvious drawbacks notwithstanding, it has proven a fairly functional way of making things run.

I’m not the first person to apply letter grades to music. Robert Christgau, the self-appointed “Dean of American rock critics,” has done it since 1967. And by now, YouTube is littered with musical tier lists — typically, in the case of Bob Dylan, made by people with far less credible claims to scholarship than I have.

So, citing the simultaneous presence of great songs (“Isis,” “Romance in Durango”), fair-to-good songs (“Mozambique,” “One More Cup of Coffee (Valley Below)”) and awful songs (“Joey,” “Sara”), I slid Desire into Bob Dylan’s B tier, just ahead of Nashville Skyline. I knew this would upset fans, many of whom rank Desire among his best.

And it did. As it did when I accused Blonde on Blonde of having “some bloat,” or when I accused most of the covers on Self Portrait of being “half-baked,” or when I pointed out that “On the Road Again” constitutes one of very few marks against Bringing it All Back Home. Through Dylan’s 1970s work, this is how the tier list looks (save one error, where The Basement Tapes should be in the #2 slot, between Highway 61 Revisited and Blood on the Tracks):

Some people who’ve seen this list have asked some variant on that initial question: Do you even like this guy? How, if I claim to be a “Bob Dylan scholar,” could I accuse any of his albums of being anything less than perfect — especially those in the B tier, all of which include their share of classic songs? How could Dylan be my favorite artist, the only singer/songwriter ever to get a Nobel Prize, and have so many albums that are so imperfect?

The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind.

Why I Criticize Bob (And Why You Should, Too)

Actually, the answer is really simple: Loving an artist’s work does not mean you should worship them like some kind of golden calf. In my adolescence, when I was first getting into Dylan’s work, that’s more or less how I regarded him. I felt personally offended whenever someone dared to write or say anything negative about his work — especially my favorite albums.

What could be more absurd than being personally offended when someone criticizes someone else? The critique — which itself is honesty, a form of love, not of attack — isn’t aimed at you. How, therefore, could it wound you?

Well, there’s the basic idea that falling in love with someone or something predisposes us against hearing them/it criticized. I know how I’d criticize certain members of my family, but I bare my fangs when someone outside the family does. When someone loves a work of art, criticizing it may feel like criticizing their taste, and consequently them. I maintain that this is a misapprehension of the act of criticism, but I understand the reaction.

Still, there’s a darker lens, one hued with a messy blend of tribalism and narcissism. The more extreme members of a fanbase — “stans,” in modern parlance — are people who have chosen a leader and, as in the days of more primitive monarchy, cast that leader as a kind of deity. Accusing them of imperfection, therefore, is tantamount to sinning against God. Or, arguably worse, people who want to see in themselves the perfection they see in their favorite artists take the psychotic mental leap of seeing themselves as their favorite artists, and view allegations of imperfection as intolerable personal affronts.

Ann Powers, whom I met at the 2019 World of Bob Dylan symposium, knows what I mean. In 2019, she published a nuanced positive review of Lana Del Rey’s groundbreaking album Norman Fucking Rockwell!. In it, Powers dared to remember that, prior to NFR!, certain critics didn’t consider LDR a “serious artist,” deeming her work “problematic, or at very least, incomplete.”

This, among other critical takes, was enough to induce LDR herself to repost the review — in since-deleted tweets, archived here — and express her dislike of the piece, Powers, and Powers’s editor (NPR, which published the review). Unsurprisingly, LDR stans took the cue from their leader and inundated Powers’s Twitter with what we’ll euphemistically call “negative engagement.”

The episode is a prime example of the narcisso-tribalism that ensues when fandom devolves into idolatry. Supporters turn into mafia-esque goons, out to destroy anyone who dares undermine the supremacy of their Don.

This kind of fandom/standom is bad for the world. It’s bad for the art world, where nuanced critical perspectives help us contextualize an artwork’s themes, techniques, and historical context, as well as our own mental and emotional responses to it. It’s bad for the arena of public discourse, where nuance serves the role of rain on the fires of riot, and without which those fires rage unabated. And, it’s bad for would-be artists, who wind up trying to create work as their heroes, not as themselves.

Criticism, Love Language

So, okay. Is letter grading a perfect way to evaluate art? Of course not. It’s not a perfect way to evaluate anything. But there is no perfect way to evaluate anything — not even, as Ann Powers learned, long, thoughtful, nuanced essays that eschew such crass gauges as letter grades.

Can you hold an artist in high regard, as I do with Dylan, and still see imperfection in their work? Of course you can. And, moreover, you should. If we consider King Lear a play of equivalent quality to Love’s Labours Lost, we surrender the ability to distinguish great theatre from fun-but-not-so-great theatre. We surrender, that is, the willingness and ability to learn, without which life is no more than getting jerked to and fro by invisible puppeteers.

The primary reason to criticize, to keep your critical instinct active and honed, is that it helps you clarify your taste. What you do and don’t respond to, what you consider virtuous and vicious — ultimately, who you are. When I grade a Bob Dylan album, I’m not telling you what is unassailably true. I’m telling you who I am.

The videos I’m posting are essentially recapitulations of conversations I’ve had in private with other songwriters. Songwriters relish these conversations: parsing our responses to classic work and arguing over which one has the littlest of edges on all the others. Not only are they fun, but they help us understand the kinds of artists we want to be. Some of us are Nashville Skylinians, writing modern, structurally disciplined country songs. Others of us are Blonde on Blondians, writing long, ungainly psychotropic poems. I don’t remotely think that making this a public exercise compromises any of these conversations’ value.

If you’re a Dylan fan at or near my level of obsessiveness, your tier list won’t look like mine. Good: Your tier list will clarify your taste, too. This project has taught me that I am ultimately a fan of poetry, of language that resonates in three frequencies at once, and therefore, I could never love Nashville Skyline like I love Blonde on Blonde.

Others will, and should, feel differently. I embrace the disagreement, and I look forward to takes that differ thoughtfully from mine. What I don’t look forward to are people who treat Dylan like a golden calf and who treat criticism like an act of war. Criticism is a love language: It shows you what you love, and by extension, how to love yourself. I’m eager to clarify my thoughts on the rest of Dylan’s studio work and probably other totemic artists’ work, too. And, whether you agree or disagree, I’m eager to hear your thoughts.

Hi Dustin- loved this article. I agree that a true super fan can hate and grade an artists work- in fact it’s like truly loving someone, you love them for the WHOLE picture of who they are and sometimes have to say hard things and set boundaries (like not listening to “Sara” haha). So I am curious, as someone who LOVES Dylan’s work in the last three decades- do you like Modern Times or Love and Theft (personal all time favorite)? I didn’t see any later albums listed on your review. I love the production, grit and rollicking of these later albums. I think Not Dark Yet is one of his best songs of all time, and my wife and I used Spirit on the Water as our first dance at our wedding. Love to hear your thoughts!!

"The answer is blowing in the wind." The best line, in a superb essay. I learned a lot. I give it an "S."